The Early History of Western Herpetoculture, Up to the Year 1900-Part 1

Intro

Jon Coote is a professional herpetologist and comparative animal nutritionist trained at the University of Nottingham in the UK. He currently resides and works primarily in the UK as a reptile product consultant but previously traveled extensively within the USA and Europe in his capacity as Director of Research & Development for T-Rex Products Inc. based in southern California. He was Chairman of the Livestock Advisory Panel for the UK’s pet industry association, the Pet Care Trust, Advisor to the International Herpetological Symposiums and previously Chairman, and past President, of the International Herpetological Society, and Chairman of the UK Charity, the British Herpetological Society, which is the UK’s oldest and most prestigious herpetological organization.

Jon used to write a regular herp column every month for the USA trade publication Pet Business News. In the past, he has written several books on reptiles and had many articles and scientific papers published in a wide variety of scientific journals, and trade and consumer magazines.

He previously attended relevant pet trade shows, and the principal reptile shows both in the USA and Europe. He takes a particular interest in attending reptile symposiums, seminars, and meetings that are relevant to his research interests. Currently, his primary research interests are the photobiology of reptiles, reptile and amphibian training, environmental enrichment, and the development of an artificial mouse flavor to encourage pet snakes to eat extruded food rather than dead mice.

Jon was responsible for the introduction of the HexArmor gauntlets in 2007 to the reptile hobby here in the UK, which enables the relatively safe handling of venomous snakes both in the wild and in captivity. Jon tested these gauntlets in the wild with venomous snakes in the USA, South Africa, and Australia. They are now widely accepted and used worldwide by both professionals and amateurs.

Jon is also a keen and gifted photographer, sculptor, gardener, miniature landscaper, terrarium decorator, and book collector, all naturally primarily concerned with reptiles!

MOAPH welcomes herpetologist historian Jonathan Coote to our museum advisory committee!

Jon has written the following, “The Early History of Western Herpetoculture” which MOAPH will publish in 3 parts starting this month.

Abstract

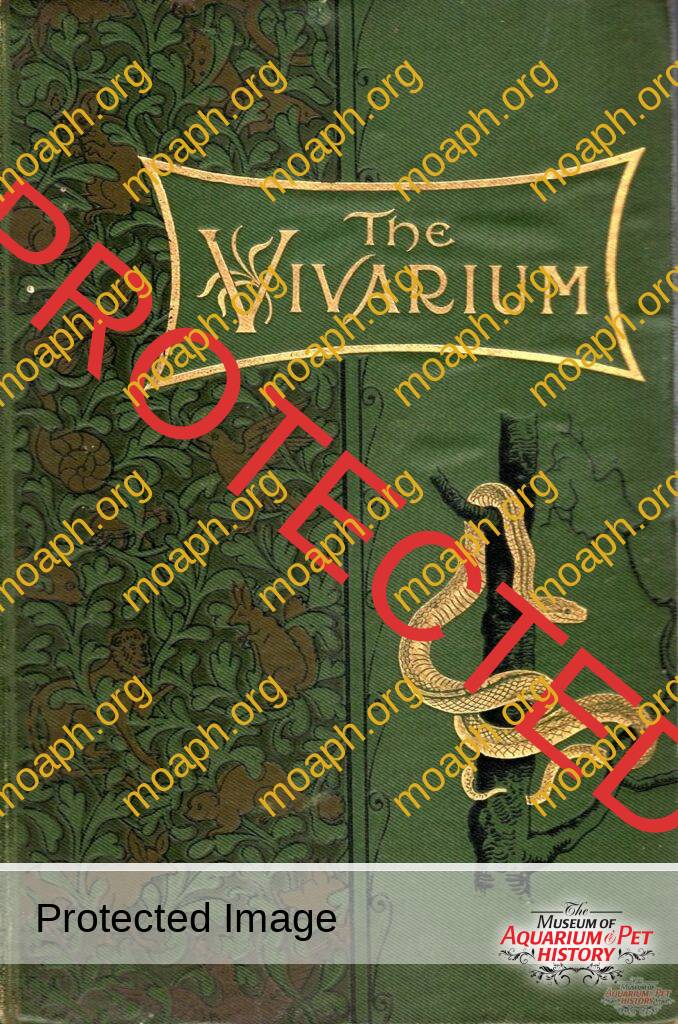

Although the world’s first reptile keepers may have been Chinese, Egyptian, or even Mexican, historical data suggests that the beginnings of herpetoculture, as we understand it, was primarily a British and European endeavor during the nineteenth century. This is indicated, by the first known specialist chelonian building constructed in 1820, the first zoo reptile house in 1849, and the first book, in English, on herpetoculture, ‘The Vivarium,’ published in 1897. The huge increase of individual wealth, as a result of the British industrial revolution and its Empire, provided the means, and the leisure, for many privileged individuals to indulge themselves in the then increasingly fashionable study of natural history, including herpetology. Increasing knowledge, higher expectations, and improved technology contributed to the success of their captive care. The data available outlines some of the pioneering attempts of these mostly forgotten, early herpetoculturalists to provide us with the foundations of the knowledge and skills that we enjoy today. Early captive breeding successes were more frequent than generally supposed. For at least one snake species, its captive breeding still remains to be repeated to this day. It is also possible to speculate, from available data, on the exchange of information between at least one of these early British pioneers and his colleagues in North America.

Earliest Records

The early documented history of keeping exotic species, including reptiles, in captivity, has always been an indication of both sufficient wealth and civilization. Also, it would appear that the skills required to keep reptiles and amphibians successfully have been gained and then lost many times through the course of human history. Early evidence of the keeping of captive reptiles is very sparse; the relatively few facts are both tantalizing and frustrating because there is not more. It is not until we get to the nineteenth century that we begin to find significant data and observations on captive care.

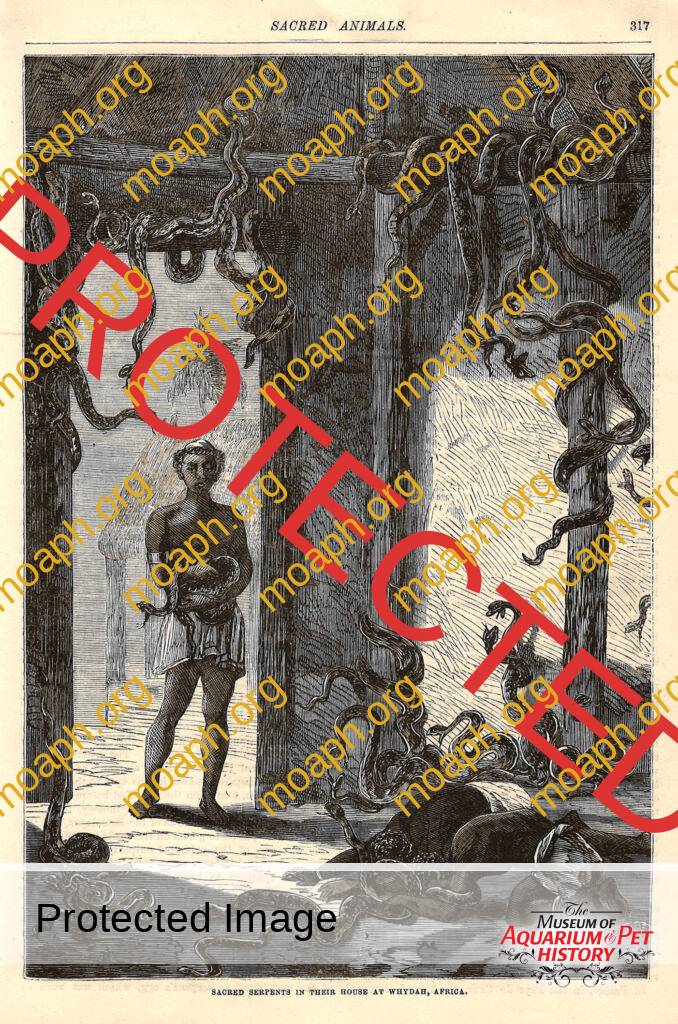

Not surprisingly, the first to keep exotic species in captivity were monarchs and emperors, having both the necessary wealth and leisure. Only much later would wealthy private individuals attempt to emulate them. Perhaps the earliest record of the keeping of wild animals, including reptiles such as cobras and crocodiles, is from the pictographs and hieroglyphs of 2500 BC, to be found at the Saqqara cemetery near Memphis in Egypt. These show that the Egyptians of the time kept a wide range of exotic species, including those that were most holy to them, and used them in religious ceremonies. The Egyptians are also the first to be recorded to have sent out an expedition to collect wild animals. Queen Hatsheput, daughter of Thutmose I of the Eighteenth Dynasty, sent an expedition to the “Land of Punt,” probably Somalia, to bring back a wide range of species. In addition to this, the Egyptian kings both received and gave a bewildering variety of exotic animals in the form of tribute with other nations.

Ptolomy I of Egypt (323 – 285 BC) was particularly interested in animals and founded a great zoo in Alexandria. His successor Ptolomy II Philadelphus enlarged this zoo and staged one of the world’s largest animal processions in history on the Feast of Dionysus in the year 285 BC, which included snakes, such as Cobras, and large crocodiles. Ptolomy II was also the recipient of a huge python that was the primary objective of a privately coordinated expedition to the Upper Nile sometime between 282 – 246 BC. This huge python was a principal exhibit in Ptolomy II’s personal collection of exotic and rare animals.

To the east, the kings of Ur kept wild animals from about 2000 BC in large walled gardens, which in the Babylonian region of Persia later became known as paradeisos, from which is derived the word paradise. The first recorded tribute in the region, from one king to another, was sent to the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I around 1100 BC. The pharaoh of Egypt sent him a gift of a large crocodile, a hippopotamus, and several ‘strange fish of the sea.’ This type of tribute, of rare and exotic animals, to presidents and kings, continues even to this day, such as Pandas and Komodo Dragons.

In China, a 900-acre walled “Park of Knowledge” was constructed sometime around 1150 BC for the use of Emperor Wen Wang in the province of Henan, which is between Beijing and Nanjing, though deer and fish were the main inmates. Subsequent emperors of China constructed similar parks until the Middle Ages, including Kublai Khan in the thirteenth century at Shang-Tu. In 1417 Yung-lo, a Chinese Ming dynasty emperor, sent an expedition from China to Africa to bring him back a live giraffe. He already had a zebra and other African animals. It is inconceivable that this same expedition would not have returned to China without the addition of many smaller species, including reptiles.

The ancient Greeks never had large royal animal collections though wealthy individuals, from the seventh century BC onwards, developed more serious and inquiring attitudes towards exotic animals that they kept, resulting in the first written information concerning a wide range of species, including reptiles. By the second century BC, wealthy Romans were keeping private collections of animals, including snakes. As early as 186 BC, a wide range of exotic animals began to be imported to fuel the gladiatorial games, including crocodiles and large snakes from Africa and other species from Northern Europe and Asia. These animals came as gifts and tributes from the governors of roman colonies, foreign dignitaries, and monarchs, but also from animal traders.

In Rome, extensive animal holding facilities were constructed called “vivaria,” usually in association with the arenas. In the third century AD, one was located just outside the Praenestine Gate. This vivarium was 440 yards long and 70 yards wide, with one long wall adjacent to the city wall. Although mainly a holding facility, it is thought that the public was allowed in to view the inmates.

Each Roman emperor strove to outdo his predecessor in terms of triumphal processions, including exotic animals and exhibitions of animals being killed in the arenas. At the beginning of the Christian era between 29 BC and 14 AD, the Roman emperor Octavious Augustus had more than 3,500 wild and tamed exotic animals from his vivaria killed in 26 exhibitions, including 420 tigers, 260 lions, 36 crocodiles, and a snake recorded as 25 yards long.

Medieval Period

In 1519 Hernando Cortés and his soldiers arrived at Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, now known as Mexico City. There they discovered probably the world’s largest royal menagerie maintained by the Aztec emperor, Montezuma. Amongst the proliferation of wildlife kept there and described by Diaz del Castillo were “vipers and poisonous snakes which had on their tails things that sound like bells. These are the worst vipers of all, and they keep them in jars and great pottery vessels…………….and there they lay their eggs and rear their young”.

The Aztecs revered snakes as important religious symbols, which is probably mainly why they kept so many of them. They also used many animals, including snakes, as sacrifices to their gods, and this may have been the main reason for the existence of the menagerie. Montezuma is, however, perhaps the first successful herpetoculturalist to be recorded in human history. Others almost certainly have previously existed in ancient history but without any surviving record.

Dial del Castillo went on to suggest that Montezuma’s reptiles were not only fed on “deer, fowls, dogs, and other things” that the Aztecs hunted but also “I have heard it said that they feed them on the flesh of the bodies of the Indians who have been sacrificed,” which confirms their religious significance in Aztec society, and the possible use of some method of force-feeding. This important and impressive imperial menagerie was totally destroyed following the conquest of the Aztecs by the invading Spanish.

Quetzalcóatl, whose name means ‘Feathered Serpent’ (cóatl meaning snake), was a very important Aztec god. He was previously a god of the Toltec people, who were conquered by the Aztecs but adopted by them into their religion. Aztec legend has it that Quetzalcóatl was originally a human being who taught the Toltecs to work metals. He was respected as a good and wise leader but was defeated by the Aztec god Tezcatlipoca, escaping into Yucatan. From there, he headed east, promising to return. It is for this reason that the Spanish were welcomed when they arrived, as the Aztecs considered them to be Quetzalcóatl’s returning party.

As a special cult object, Quetzalcóatl was perceived as the god of wind and of both the morning and evening stars. He was credited with creating the world, creating humanity and providing it with corn, and also, more bizarrely, with inventing the calendar. He was one of the few Aztec deities that did not require human sacrifice. Sacrifices to him were generally confined to snakes, birds, and butterflies.

In Europe, during the Middle Ages, the requirement for large numbers of exotic animals diminished with the decline of the bloody Roman spectacles, and once more, it was royalty and wealthy merchants who indulged their passion for unusual pets. Henry I of England, the youngest son of William the Conqueror, in about 1100, established the first recorded Royal menagerie in England at Woodstock. Later, King John (1199 – 1216) continued the tradition during the Crusades and at the time of Robin Hood. In 1243, William de Botton became the first recorded animal keeper of the Royal Menagerie. It became normal for a nobleman to assume this position in the collection’s earliest years.

In 1231 the Holy Roman emperor, Frederick II von Hohenstaufen, leader of the Fifth Crusade, had established the first great European menagerie of wild animals at his court in southern Italy. In 1250 Frederick sent his brother-in-law, Henry III of England, a gift of three Leopards. A manuscript of the time at the College of Arms says – “Since the arrival of three leopards in London in 1250, there are constant records of payment made for maintenance of the animals at the Tower”. The payment was six pence per Leopard per day (three cents) and three halfpence per day for the keeper (less than half a cent). These three leopards have become forever immortalized in the royal coat of arms of the kings and queens of England since that time. In 1252 Henry III transferred the animals at Woodstock, established by his predecessors, to the Tower of London. In 1255 he desired the Sheriffs of London to build a house for an elephant at the Tower sent as a gift to him from Louis IX of France: “We command you that, of the farm of our city, to cause, without delay, to be built at our Tower of London, one house of forty feet long, and twenty deep, for our Elephant.”