The Forgotten Aquarium of Rome – Part 1

Although it fully deserves to be included in the list of the early public aquariums, the protagonist of this article is practically unknown to most aquarium history buffs. I am referring to the Acquario Romano, inaugurated in the city of Rome on May 29, 1887.

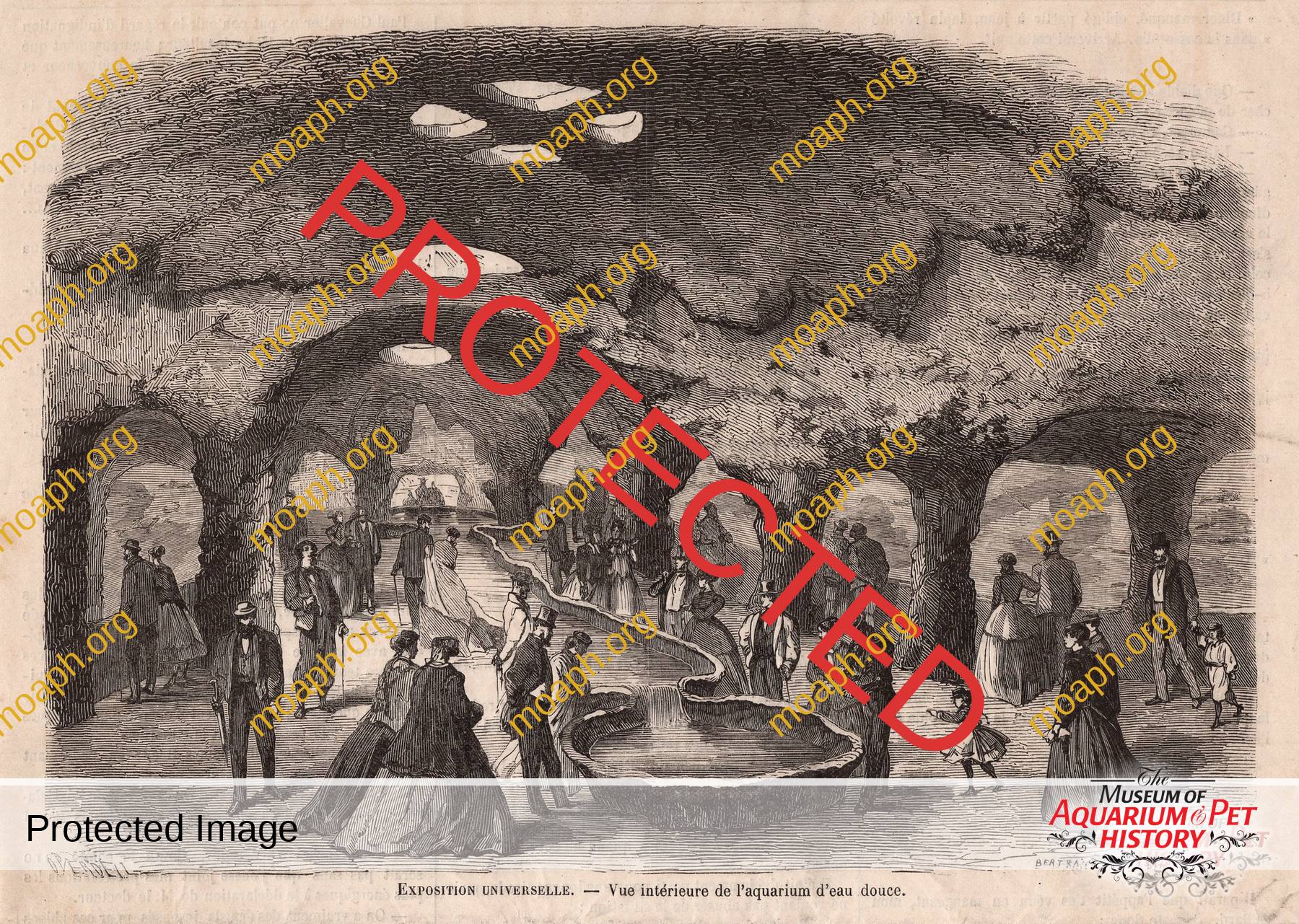

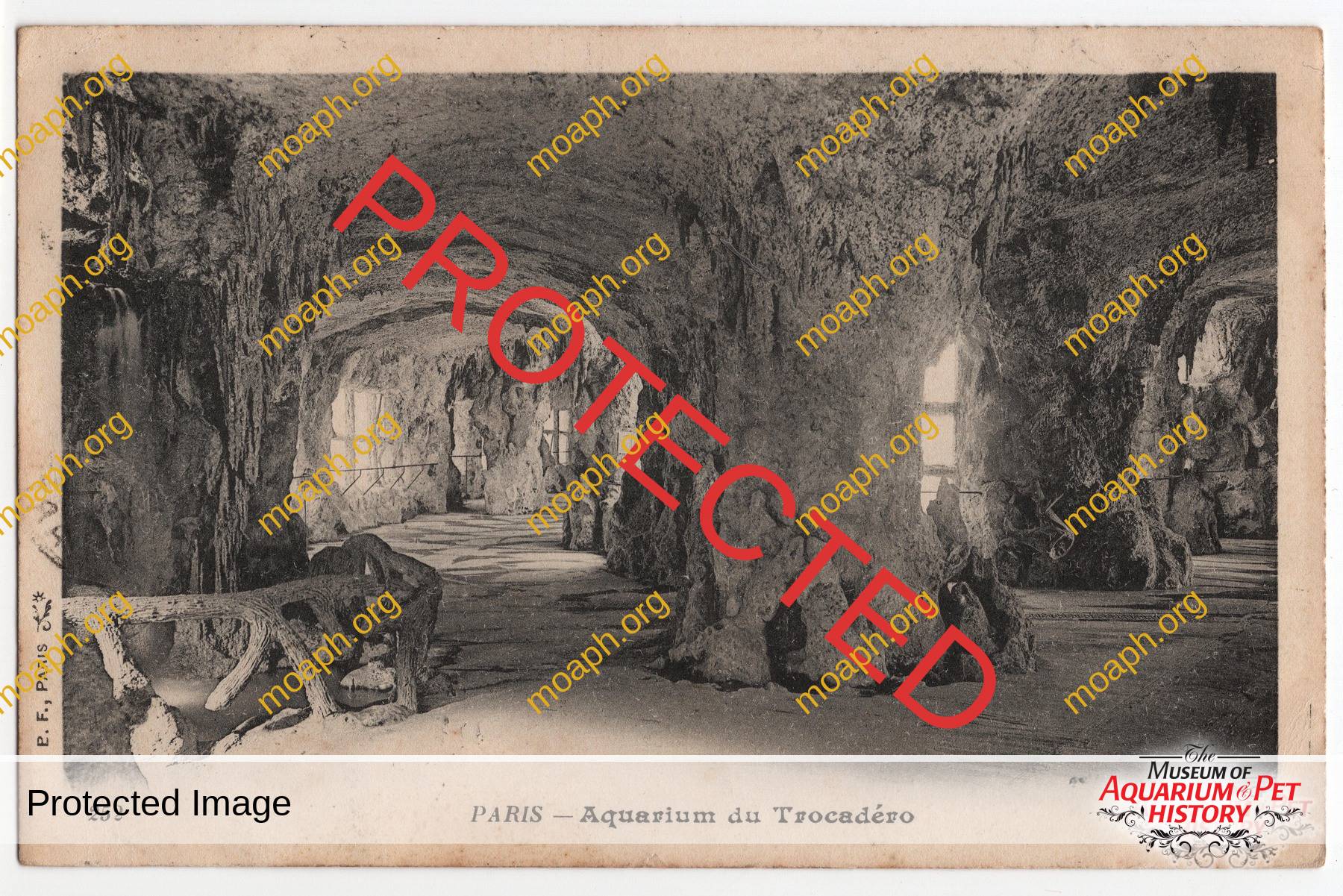

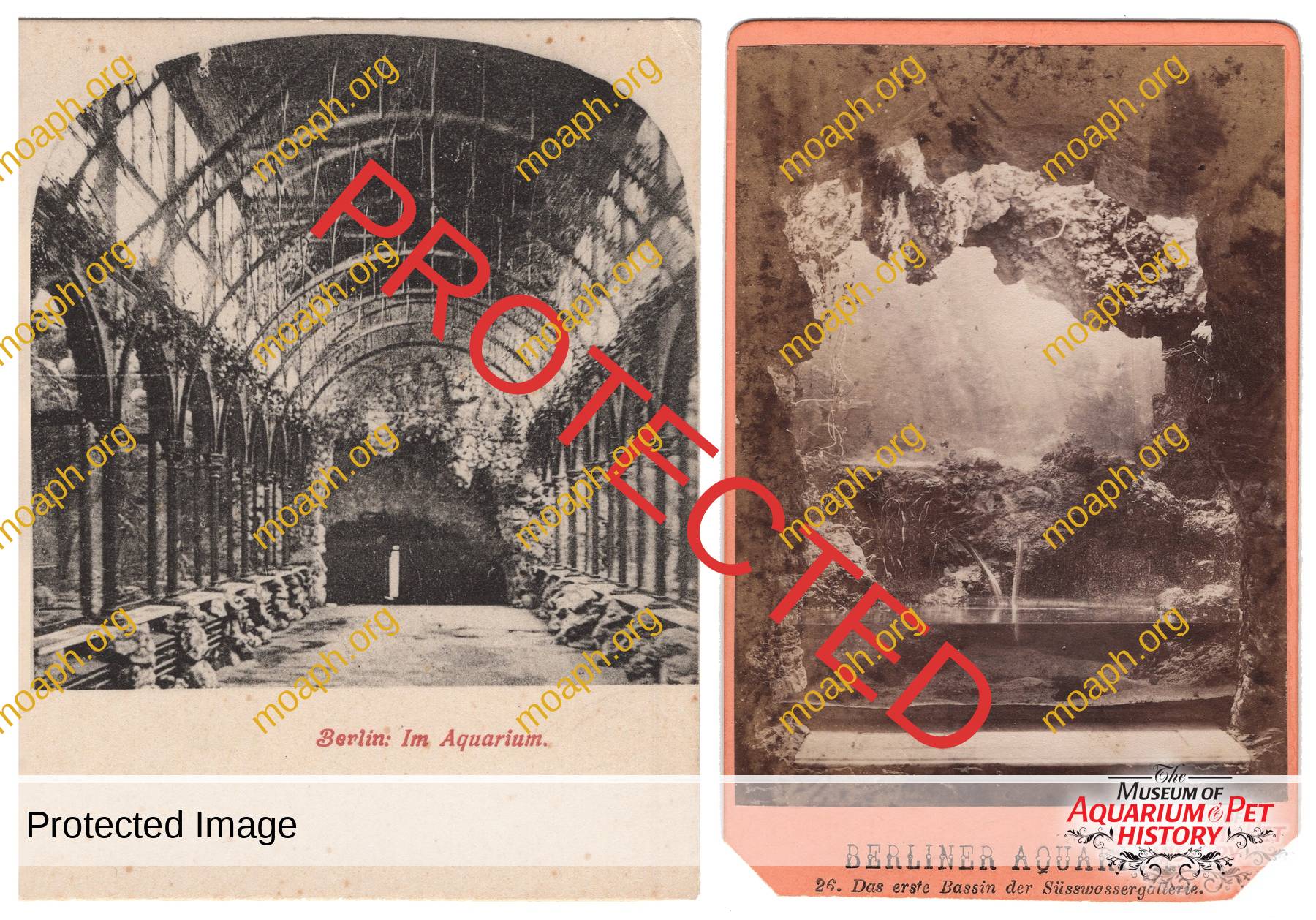

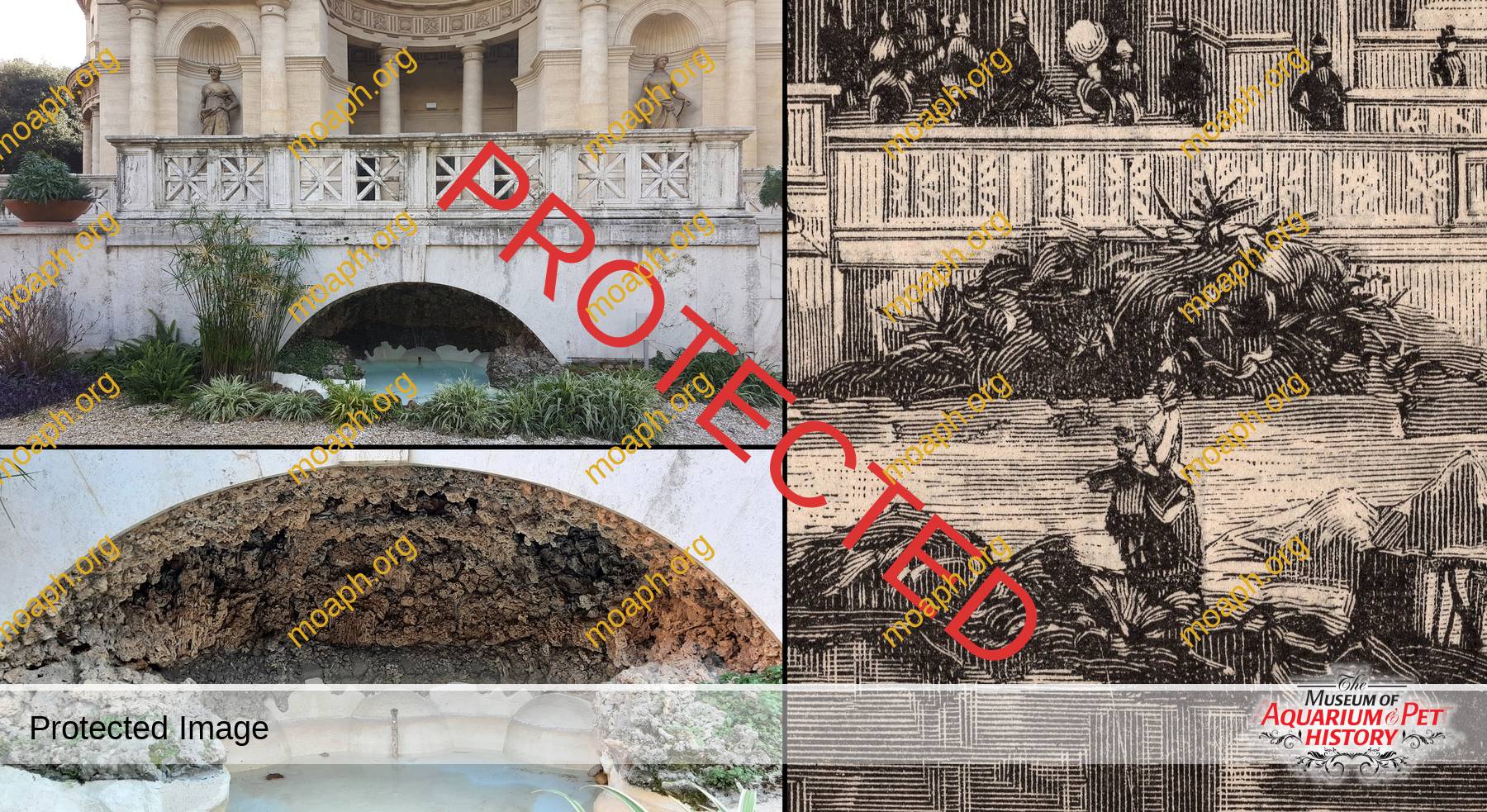

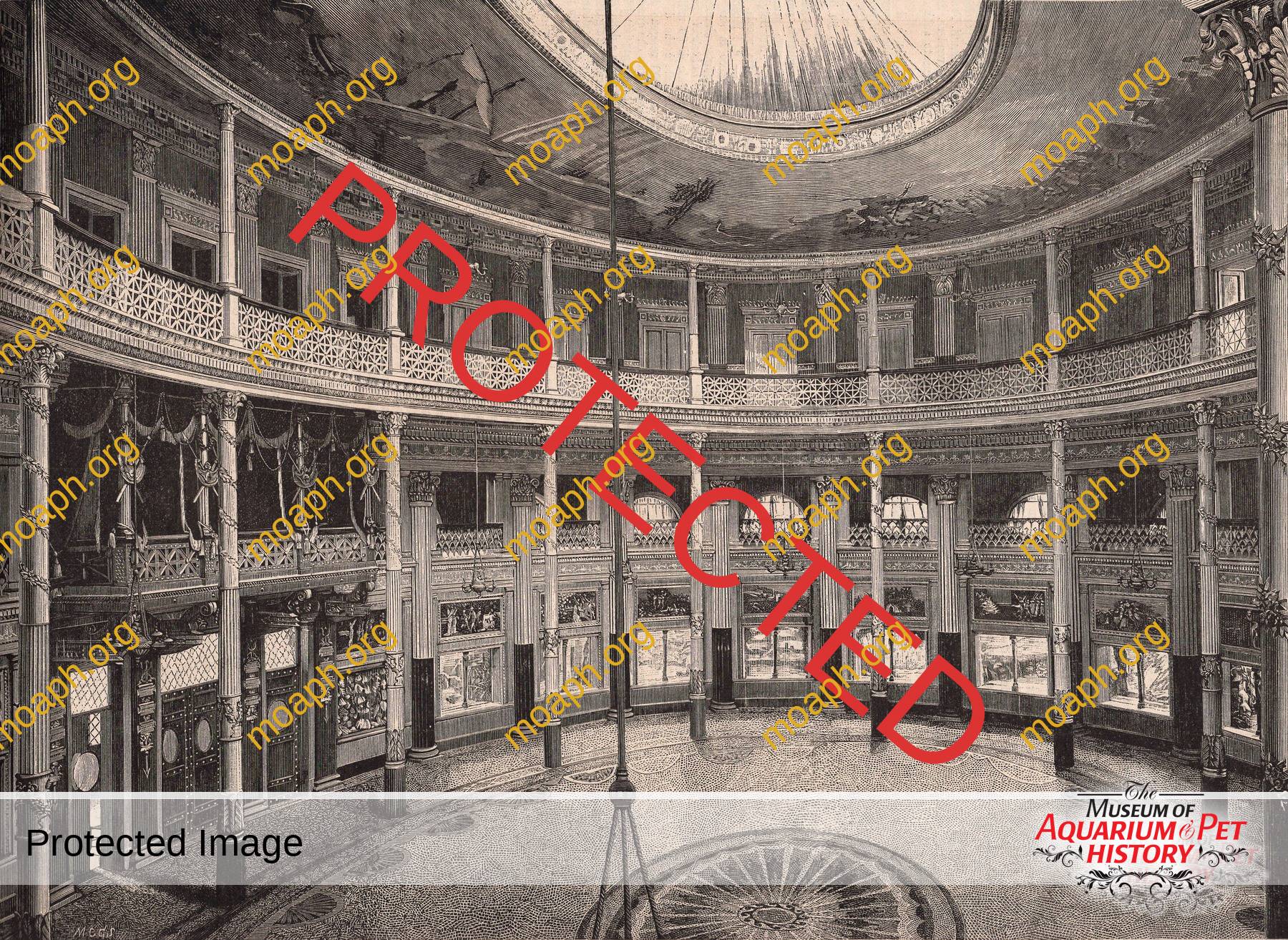

That day its visitors, after crossing a pretty garden including a pond with protruding rocks (actually they were ruins of ancient Rome!) and two rustic footbridges, were greeted by a sumptuous, bright, and extraordinarily elegant building. In other words, a very different place from most of the Continental public aquariums built since the mid-1860s, which had interior spaces similar to a complex of caves, or to a gloomy basement.

The historical context

Even though it hasn’t housed fish for over a century, the Acquario Romano still exists today, off the radar of tourists who, captivated by the beauty of more iconic monuments of the “Eternal City”, mostly ignore its existence. The citizens of Rome themselves usually know little or nothing about it.

The troubled events of this forgotten aquarium began in the Kingdom of Italy (starting from now we will simply refer to it as “Italy”), a unitary state that, nine years after its proclamation in 1861, annexed the Papal States, thereby strongly reducing the temporal power of the Holy See.

Rome, a city frozen by the papal stagnation for too long, became the new capital of Italy in 1871, the year traditionally considered as the end of the Risorgimento, the 19th century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian peninsula into a single state. The Minister of Finance at the time, Quintino Sella, immediately wanted to lift the city to the same level of other important European capitals, promoting a policy of building development and support for new productive businesses. One of his main goals, as a man of great culture and confirmed secularist, was to make Rome a “center of science” full of prestigious places where to teach and promote it.

Woodcut showing the Acquario Romano and its garden, published by the newspaper L’Illustrazione Italiana on June 5, 1887. The building looks like a combination between a triumphal arch and an amphitheater.

The original entrance on Cattaneo Street. The 1887 woodcut from the newspaper L’Illustrazione Italiana (vol. XIV, No. 23) clearly shows the pond and one of the two rustic footbridges that crossed it. In time of war, the cast-iron fence surrounding the entire facility was completely removed to support the country’s military effort.

A persuasive man and his business venture

Realizing the entrepreneurial opportunities that could derive from this political and ideological guidance, starting from 1880 a man coming from the Italian city of Como began with great obstinacy to propose to the Municipality of Rome to build a facility that, according to the final project, would have offered to the city:

- a fish farm to produce and sell “healthy food at low cost”, and fry for other farmers and for the repopulation of some Italian rivers and lakes with serious pollution and overfishing problems

- a fish farming school

- a pond where people could also fish (catch and eat practice!)

- a public aquarium.

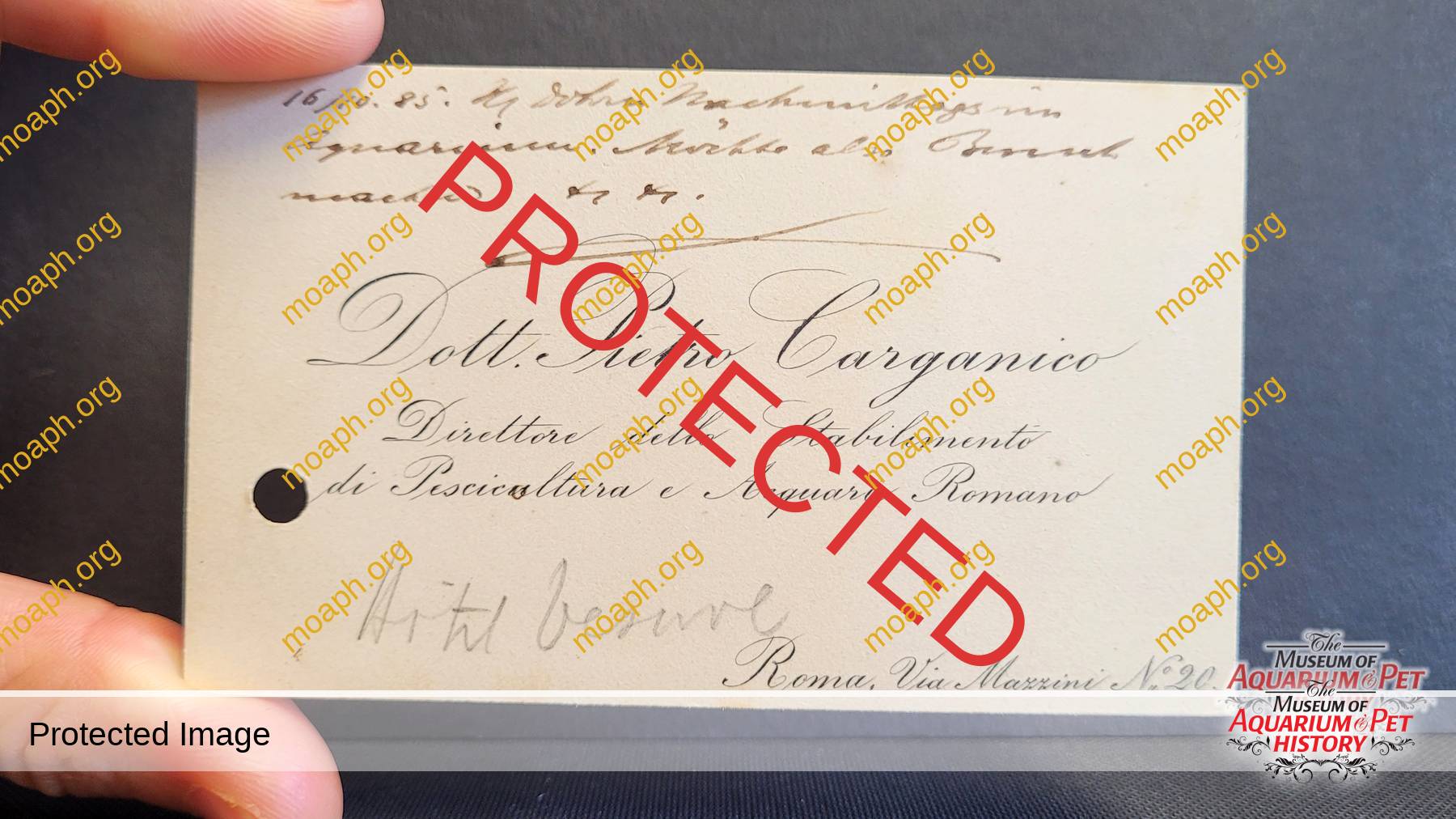

His name was Pietro Carganico. About this mysterious figure, very little is known. Despite my efforts, I have not been able to find any photograph depicting him, any detail about his professional experience prior to and after the Acquario Romano venture (with the exception of fragmentary information about a silkworm farm he probably managed), or any living relative.

However, there is no denying that, in spite of his “supposed” poor references, technical expertise and financial resources, he showed great perseverance and persuasive skills, to the point of getting a positive opinion on July 12, 1882.

After suggesting at least a couple of other locations in the historical center of Rome (one of these was in Nazionale Street), Carganico got a 30 years concession for the rectangular Manfredo Fanti Square, in the Esquilino district, a residential area of the city whose building development had started ten years earlier with the aim of hosting the elite of city’s bourgeoisie. The agreement was signed on December 1, 1883.

Under construction

In order to raise the funds needed to make his dream come true, Carganico asked both the municipal administration and private investors, among whom there were also building contractors working in the city and, in particular, in the Esquilino district. Once again, his persuasive skills worked.

For the design of the final plan, and for the direction of construction, the company Pietro Carganico & Co., also mentioned in old documents as “Società Romana di Piscicoltura ed Acquario,” confirmed the architect Ettore Bernich and the construction company Cavadoni & Deserti.

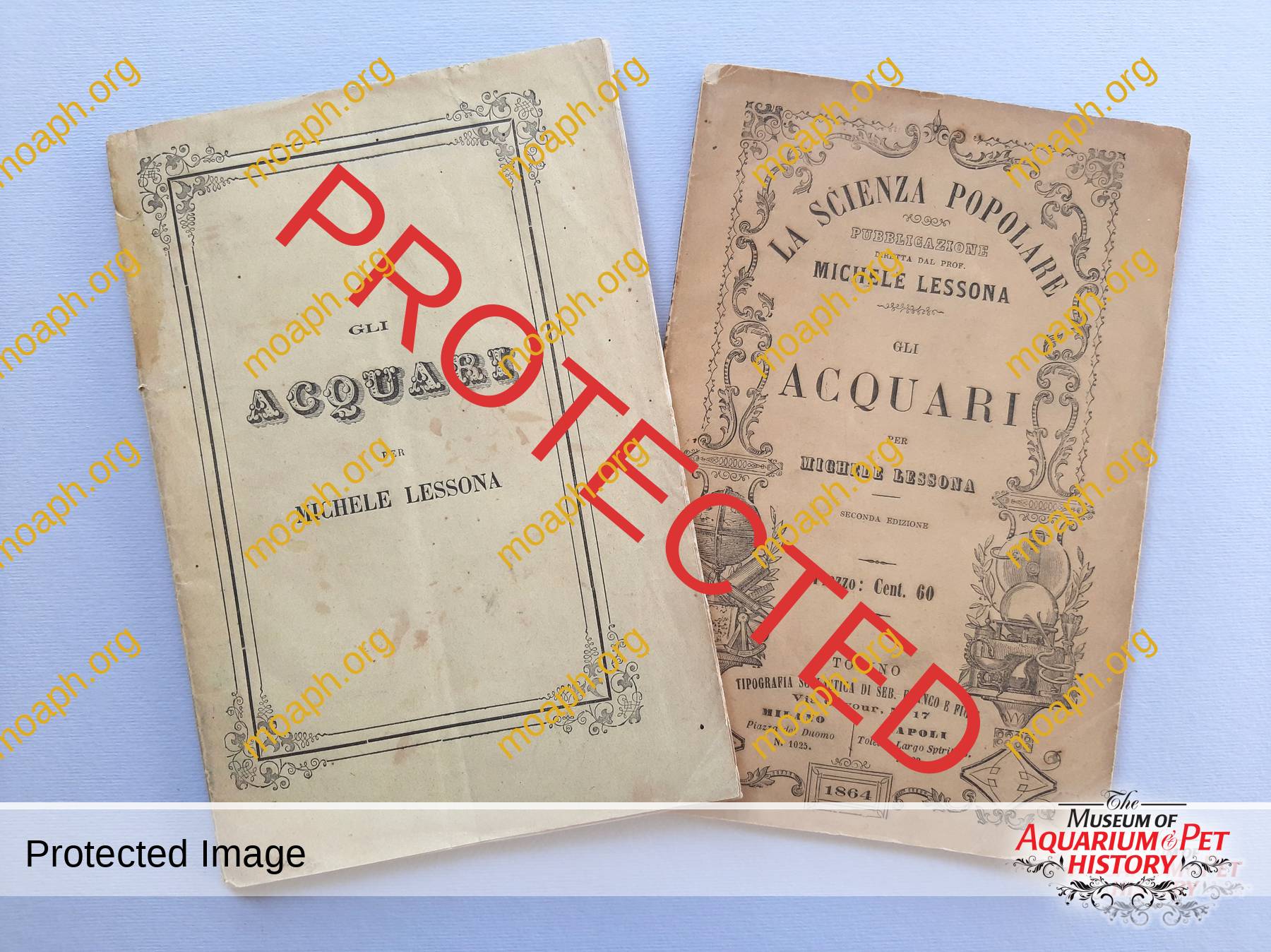

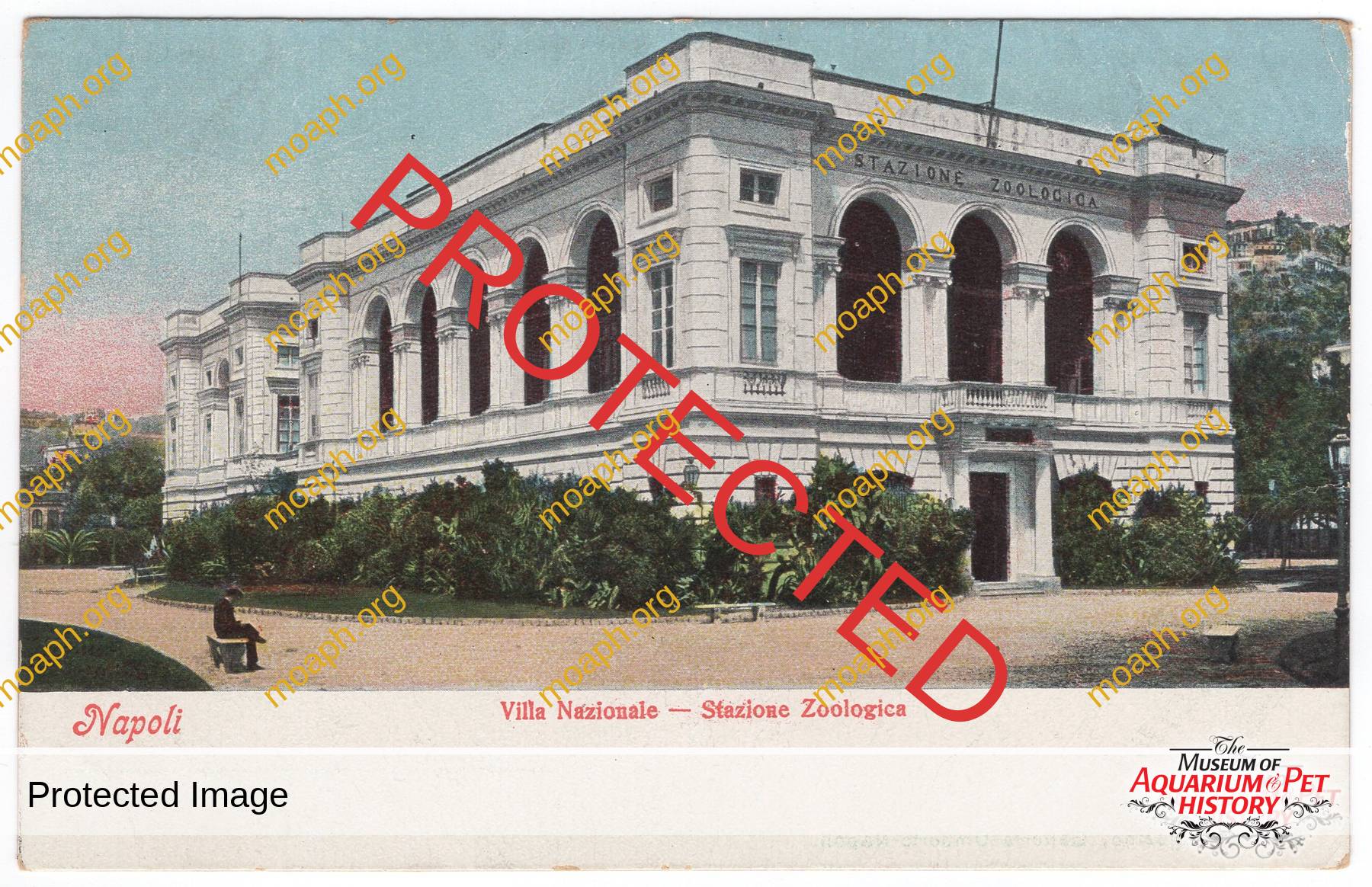

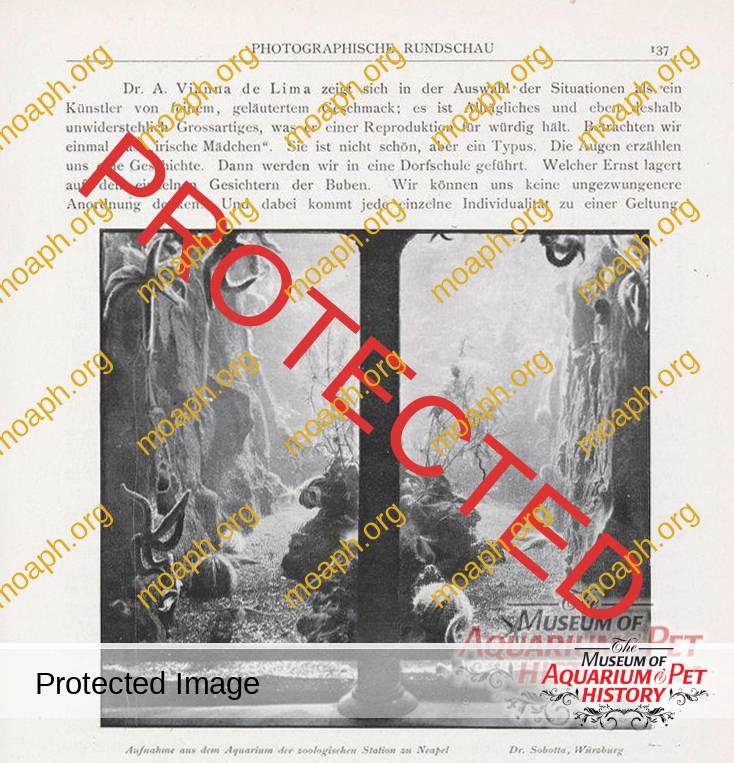

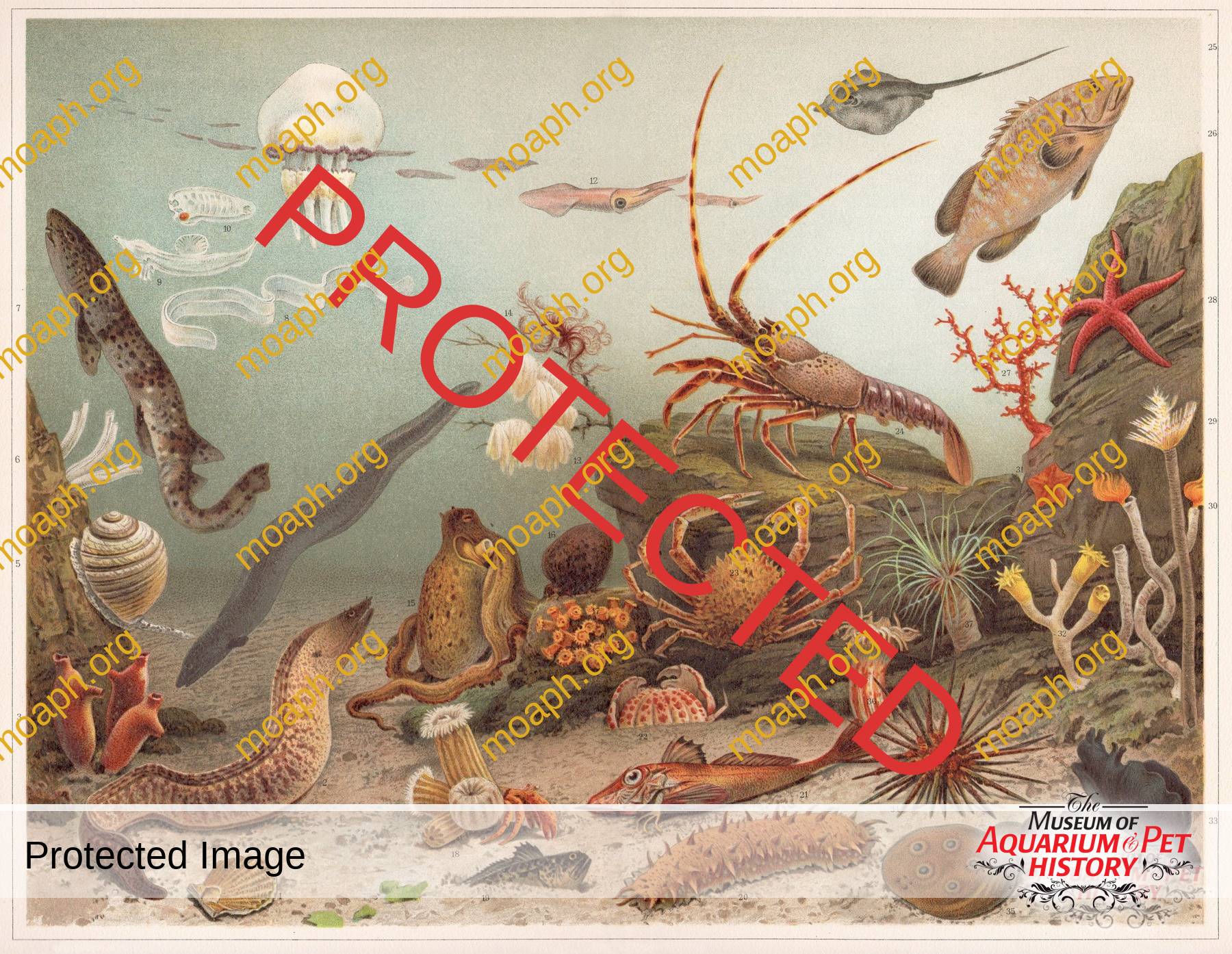

Back then, fish shows and public aquaria were a risky business, often not profitable or long-lasting. Furthermore, the aquarium craze had never infected the Italians (in this country, the aquarium hobby slowly developed after WWII), just consider that in those years there was only one aquarium book printed in Italian and written by an Italian author (Gli Acquari by Michele Lessona). If you wanted to see some fish tanks with their inhabitants, you had to visit the public aquarium opened in 1874 at the Zoological Station of Naples.

Both Pietro Carganico and Mr. Deserti, the latter builder and shareholder of the Acquario Romano, visited the Zoological Station and got from its founder Anton Dohrn a technical consult on how to build and set up the show tanks, the circulation systems and the filtration units. It’s reasonable to assume that Dohrn also provided helpful information on the best German and English suppliers of glass, hydraulic pumps and engines.

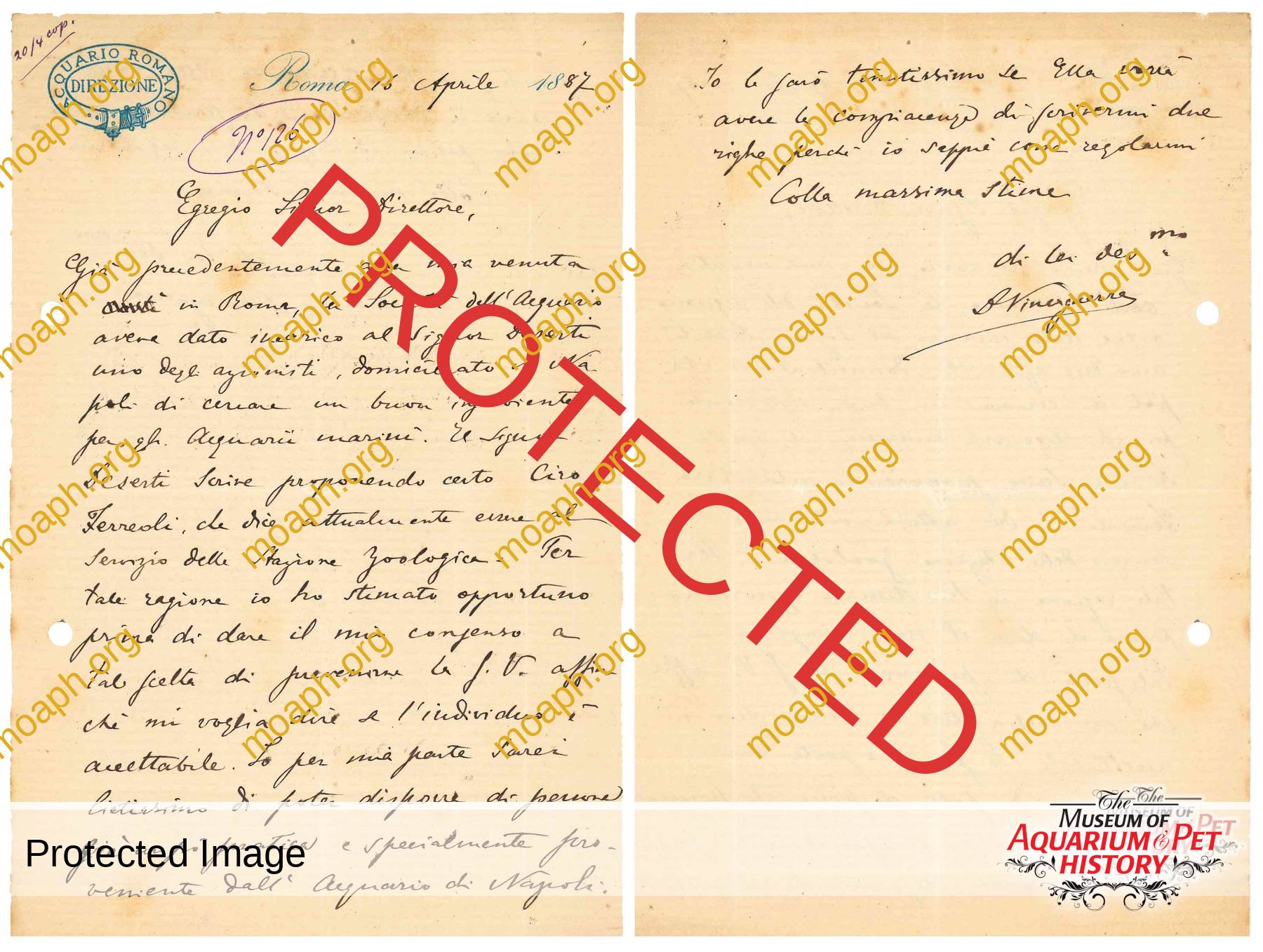

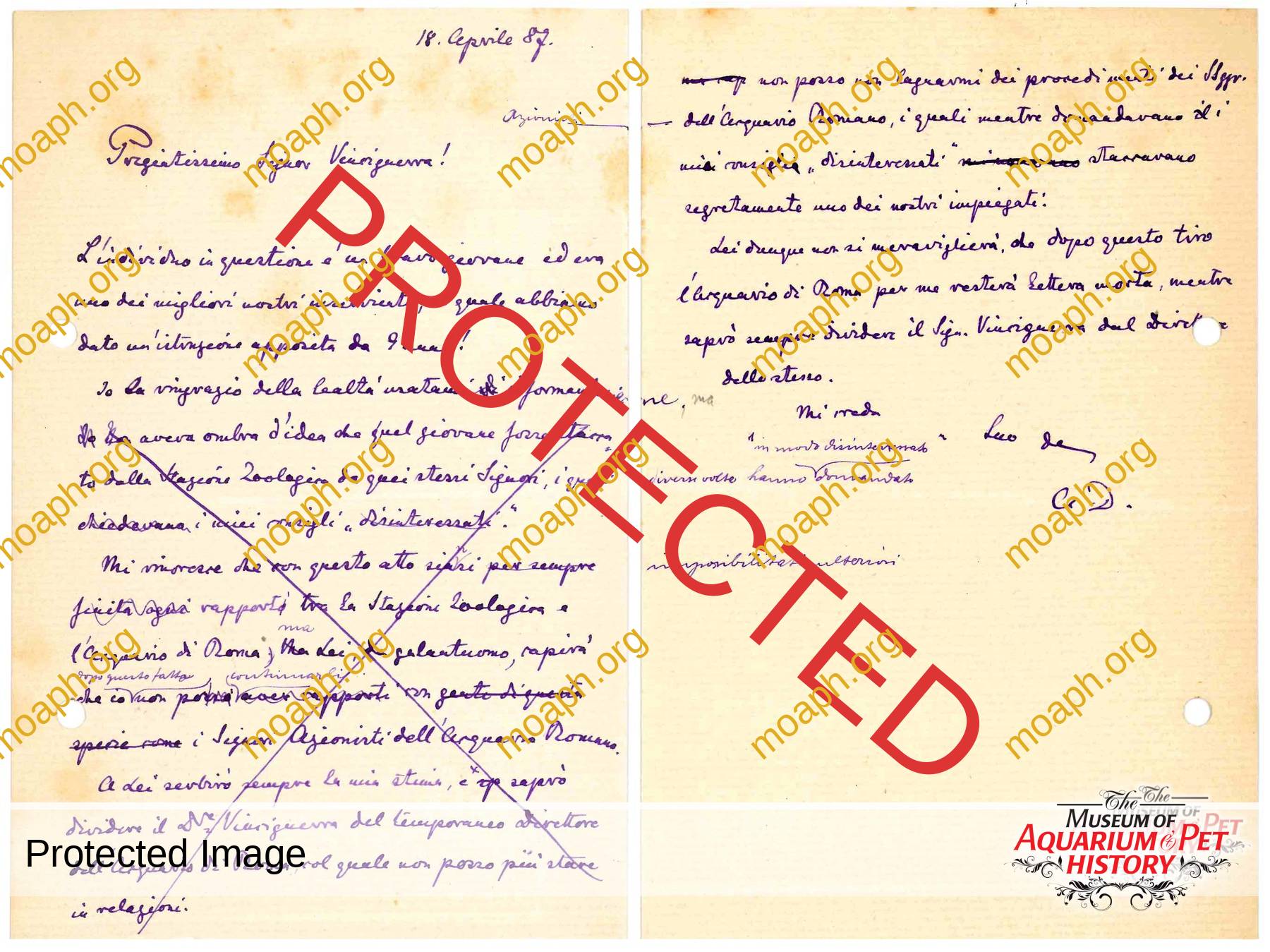

Dohrn, a man of honor, would sever his cooperation in April 1887, once he realized that the Acquario Romano management was sneaking behind his back for quite sometime to hire away Ciro Ferreoli, one of the best aquarists working at the Zoological Station.

The construction of the Acquario Romano started in 1884, and officially ended on May 21, 1885.

Risky choices

Looking at the distribution of the spaces and at the aspect of this facility, I realized that Bernich probably did not have the professional know-how as to what was needed to make a fish farm productive and economically sustainable. The pond, frankly, was of modest size, capable of only fulfilling an ornamental purpose. The concrete vessels of the hatchery had been confined in the basement and were probably of insufficient number and capacity. Around the building there was a non-specified number of underground containers, it is hypothesized not particularly large, and a water stream of little benefit.

As a second hypothesis, one could think that the investors, in particular the building contractors with economic interests in the Esquilino district, strongly influenced Bernich in making some specific design choices. As already mentioned, the building development of the district started for the middle-class of the time, but things changed, and year after year the area was settled mainly by working-class families. For this kind of public the investors possibly started to ask for “less science and more entertainment”: meeting places, gardens, multifunctional facilities for exhibitions, concerts, dances, theatrical performances, catering activities, etc.

Finally, it cannot be ruled out that Bernich, after getting essentially a blank check from the “unprepared” Carganico, simply took the opportunity to give free rein to his eclectic creativity, building an expensive masterpiece that, although not corresponding to the functional requirements of the project (thus not respecting the commitments made with the Municipality of Rome, even risking the revocation of the concession), would have been an extraordinary resume builder for him. In fact, today Bernich is remembered above all as “the designer of the Acquario Romano.”

Whatever the truth, I wonder why Carganico approved Bernich’s plan. A true expert in fish farming would have immediately asked to revise everything, right from the early drafts. Even before that, a professional in the field would have realized right away that Manfredo Fanti Square perhaps wasn’t large enough. Moreover, Carganico’s main interest was just the fish farming establishment, not the aquarium. Probably, the tight deadlines for the presentation of the final plan to the Municipality of Rome and the pressure from the investors did not help him to face everything with the necessary lucidity.

In 1867, the Aquarium de Paris was arranged in the disused quarries near the prior Universal Exhibitions of Paris. The subterranean aquarium site was made up of old quarries that had served to shelter a part of the cavalry of the Emperor. The original grotto-style section of the aquarium was built underground using imitation concrete rocks.

The Aquarium du Trocadéro (Paris), 1878. The European public aquariums of the time often had indoor spaces similar to a batcave! Where it wasn’t possible to exploit real grottos or other underground locations, a load-bearing metal framework was built to which real rocks, or imitation concrete rocks, were then attached.

On the Berlin Aquarium, an iconic example of grotto architecture, the historian Albert J. Klee, Ph.D. wrote: “… there are everywhere huge masses of rock imported from great distances at a great cost, but answering no real constructive purpose whatever, or supporting merely that which could be supported by iron columns of one-tenth the diameter of the piles of stone.”

Gli Acquari by Michele Lessona, the first aquarium book published in Italian by an Italian author. First (1862) and second edition (1864).

“Unexpected” change of ownership

But let’s go back to the end of the building construction, therefore to 1885. The inauguration was scheduled for that year, but something unfair happened, freezing everything. What we know is that on June 30, 1886, Carganico was forced to transfer the concession of the area, and the ownership of the building with its garden, to the company known as Società Anonima dell’Acquario Romano, probably founded by some of the original investors of the Aquarium. The Municipality of Rome received the official notification of the change of ownership and management on March 15, 1887. The matter had legal repercussions that led to a two-years delay in the in inauguration of the facility. Carganico expressed his disagreement through newspapers as well, and the Società Anonima dell’Acquario Romano replied, confirming that Carganico had received a large sum of money to leave the project, together with the promise that a commemorative plaque with his name would be placed in the Aquarium.

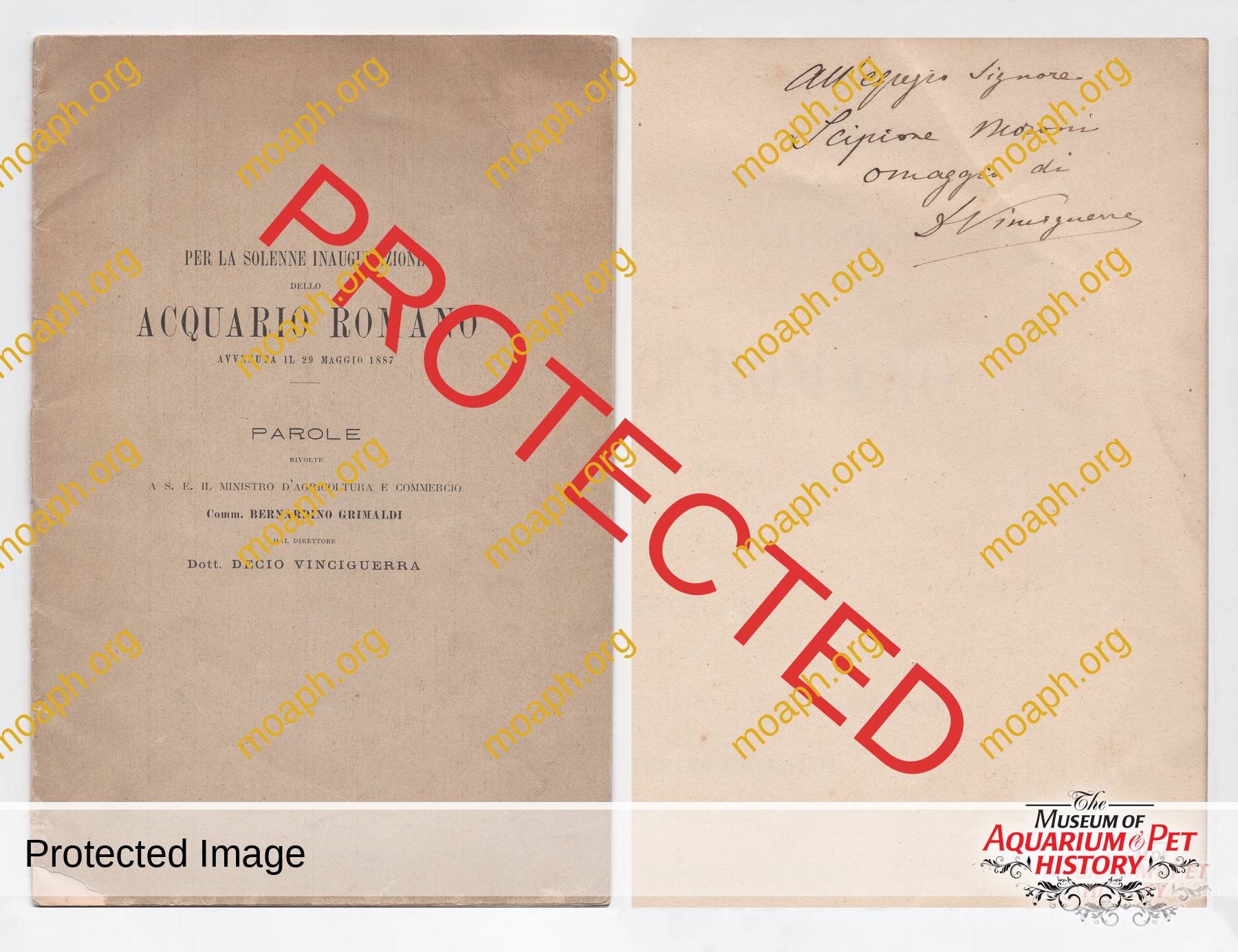

To fill the role of director of the Acquario Romano, the new ownership hired Decio Vinciguerra, an ichthyologist from the city of Genoa. A few days prior to the inauguration, Vinciguerra showed the facility to investors and journalists, thus the opening date was announced by various newspapers, and also advertised through a chromolithographic poster designed by the talented artist Marchetti and printed by the Barberi lithographic studio. It was placed in several parts of the city and, without a doubt, today it represents the Holy Grail for people collecting antiques related to the history of this public aquarium.

On April 16, 1887, Decio Vinciguerra wrote this letter to Dohrn with the aim to inform him that the Acquario Romano management was interested in hiring Ciro Ferreoli, a talented aquarist working at the Zoological Station of Naples for 9 years. Dohrn didn’t take it well. Vinciguerra also asked him to confirm Ferreoli’s credentials, an inappropriate, almost provocative request which probably upset Dohrn even more! Copyright: Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn – Archivio Storico (ASZN, A 1887 “V”.126.)

Dohrn used to keep a handwritten copy of the outbound mail. Here is the draft of the letter he sent to Decio Vinciguerra. Dohrn used harsh tones, confirming that after giving his cooperation to the Acquario Romano he would never expect such an unfair behavior from its shareholders, including especially Mr. Deserti. By this time, Dohrn had broken off any relationship with the Acquario Romano. Copyright: Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn – Archivio Storico (ASZN, A 1887 “V”.127.)

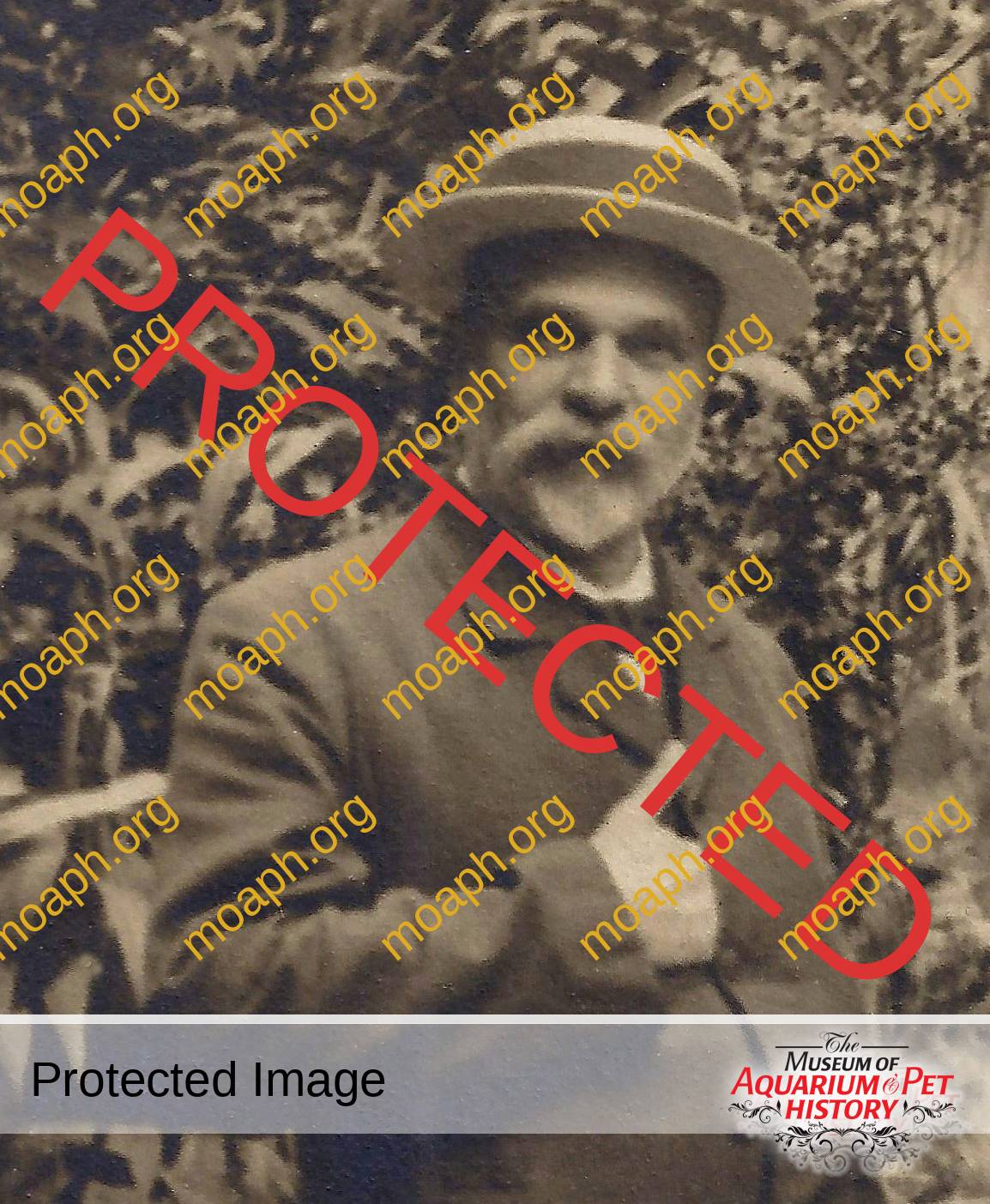

Decio Vinciguerra, the director of the Acquario Romano. Courtesy of Civic Museum of Natural History “G. Doria”, Genoa.

The iconic doors of the main hall.

Entering the Acquario Romano.

The Acquario Romano in all its magnificence, exactly as it appeared to the first visitors on the inauguration day. The vault showing mythological subjects was painted by the artist Giuseppe Toeschi. Unfortunately, due to water damage it was replaced in the 1930s by a less elegant false ceiling. Woodcut published by the newspaper L’Illustrazione Italiana.

Present and past.

Inauguration

On the inauguration day, the king of Italy Umberto I was not present. The ceremony was attended by the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce Bernardino Grimaldi, who gave a brilliant speech, followed by the talks of Vinciguerra and Rivaroli (lawyer and president of the Società Anonima dell’Acquario Romano). It seems that none of the three speakers mentioned Carganico.

Despite the condensation on the glass, the twenty aquariums on the main hall amazed and delighted the public. Half the tanks had a marine set-up, and were populated by animals from the Tyrrhenian Sea. A newspaper of the time, the Il Fanfulla, confirmed the presence of octopuses, morays, crabs and lobsters. Rome is quite close to the coast, so it is likely that the supply of these and many other species was not excessively difficult, especially during the cold months of the year.

End of part 1.